The Sound of Black Voices, The Sound of My Father

I.

Who Will Build this Ark of Bones ?

Once upon a time I had a house full of cousins, convivial aunties, resounding uncles with gold belt-buckles and big happy teeth, a black grandmother who washed my hair in the sink and taught my mom how to cook greens so tender and comb through my coils. On Sundays we’d all be at the local Baptist church, the whole choir was blood, I would clap and spin and scoot up to the stage in a rile of girlhood and pride, dad would be leading everybody, being the commanding, larger-than-life, chief-of-a-loving tyrant that he could be, for the good times. Nothing mattered but the tone when he got to singing—no one should question the authority of a voice like that, the fear that it would go silent was enough to convince us to endure every scream.

One by one those bodies visiting our house turned into ghosts, figments of my imagination. Day by day our routine was slipping into disaster’s taunting shadow and it seemed everybody was waiting for dad to fulfill a prophecy and enter the afterlife, sing to us from the other side. When he did, his haunting compliance so well-timed it’s my eternal fable for unconventional acts of deep generosity, my mom and I were out in California having left the paradise of phantoms I called home for a safer environment, a less complicated dream. By the time we got word, our Iowa fairytale had turned into a Reparations graveyard.

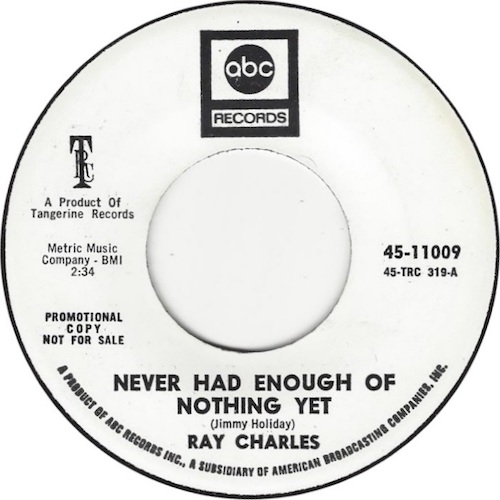

Maybe they weren’t legal heirs to the rights to his songs but my grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins, deserved something—a gold record, a Stetson or fringed suede and denim jacket, one of his many guns packed in a suitcase like grams—that announced Jimmy was here, was ours. By the time it was my mom’s turn to look through the remaining belongings all that was left was her stuffed childhood monkey, Zip, some pictures and letters he’d written me and her in his broken penmanship, and a shoebox full of tapes he’d been keeping under their circular bed, recordings of his latest music.

Enough for a new beginning.

After all, his voice remained immortal, black with grief and guile, sweet and childlike, chills down the spine, gritty and remote, knowing when it’s time to tremble and when to be still in the low of limbo.

II.

Can’t You Hear It?

Listening, knowing one another by sound and voice, is the first law of black liberation—without this skill there is no self-preservation. From differentiating between urgent aggression and routine to separating moments of life-threatening anguish on a slaveship from the casual agony of another day in the hold, from deciphering the outcome of a session on the auction block through the cadence of those in attendance bidding in, to listening for the music of keys and shoes and rippling bills of sale and commands, all while still in disbelief at having become human contraband.

Next came the soul-threatening business of navigating life and forced labor on plantations, using the well-tuned ear of black survival to decode a symphony of footsteps, whips, Bible verses, moans, hisses, work chants, screams, hooflandings, rainfall, collapse, talking drum rising from the tap-rooted foot to the shamed skull, all of it echoing in the trapped and huddled sound of the English syllabics mangling in the planters’ mouths, acting as one of many indications that violently broken logic was the fulcrum of the West and would be used to keep black bodies in captivity in one form or another, for as long as circumstance or the bodies themselves would abide. And if we listened closely enough to that cacophony, we could detect within it the performance of hatred and domination used to mask the violent, obsessive, almost fanatical love American whites harbor for black bodies, black people, and everything we produce—how they tend to often covet and resent all otherness for the trance of envy or awe it strikes in them. We who hear this grand hypocrisy with our whole bodies are the first fugitives from it, running and not in fear.

“That box of tapes my dad left opened up a life of listening to the recorded voices of black people, developing almost pathological kinship with resonant timbres.”We had to learn to listen through the wall of their deflected self-loathing on the road to turning their heroes and healers—us—into capital, before we could even hear ourselves think. We had to improvise small acts of subversion and freedom using our sensory attention and then project that provisional understanding of where we had been taken and why onto our own musical and spoken and mimed forms as we invented songs and styles of movement to relay the stories our hushed listening helped us gather and remember and invent. Our music became a form of collective listening and we used it to deliver dire messages as well as just to cope and retreat into beauty in otherwise-wretched places.

Learning to read could get us killed on plantations, but a literacy in rhythm and tone so acute we could communicate several very different intentions in one five-word arpeggiated blues phrase, was lost on those too literal, too evil to hear truths they didn’t comprehend: watchmen and slavers. And anything they could not ruin upfront became our grail, our pastime paradise, salvation. The improvisational musics we invented under those hyper-traumatic circumstances—deep listening projected outward, become mirrors to our jailers, deleting their obscene vanities, exposing them to themselves by inventing pure sonic opposition.

III.

Alone Together

My own listening practice began early and as a matter of survival and generational reckoning, because I was born into a household brimming with music and conflict, to parents who were either up all night singing and testing chords on the piano, or up all night fighting, with little in between. Everyone was acting funny, all the adults around me were a little lost and crazy—so not only was I both spy and informant for both sides, I was ruthlessly neutral; no one seemed like a victim and at the same time everyone did, and l listened closely.

Before I was three, I’d learned to listen for quarreling between my parents and decipher its severity. I knew how to listen to figure out if dad was sleeping and if so, with or without the phone off the hook. I could tell by the energy in his voice what kind of mood he was in, manic or brooding, and I could tell if mom was hysterical by the pitch of her moments of catatonia. I had to listen to my own breathing or lack thereof to block them out, the acoustics of survival that traveled in my DNA were needed in my household, where the race and gender problems played themselves out in microcosm and became inverted: the black man was in charge here and also petrified of the creative power that guided his rule; the white woman was his willful slave and not meant to get away. I was the evidence of what they could not otherwise say, that life begets life and it’s okay.

I listened in my sleep, my subconscious a vigilante. I’m not exaggerating. I developed a kind of clairaudience that helped me remain one step ahead of the misguided adults around me, I could feel them unraveling acoustically before they knew a new shambles was closing in on them, and I could dazzle them with my innocence just enough to remind everyone who the child was, who was responsible for whom (though I also learned that it’s a blurry equation, responsibility, everyone is everyone’s burden). I had to be responsible for my own psychic protection and it made me feel close to my ancestors—before I even knew their story, I felt it, was guided by events I had not lived in this lifetime, and the guidance came in the form of sound awareness, a kind of keeness no one taught me, born of necessity. Listening offered the distance and dimension I needed to endure, it’s how I drew a boundary around my body in that chaotic space, how I came to be a form, why I am a destiny.

IV.

The Man’s Gone Now

There’s an undeniable connection between close listening and absence, a sense that something is missing or has been stolen from us and might be tiptoeing toward us in the night from an unnameable erotic distance, pursuing triumphant reunion. This quiet almost anti-social optimism needs a place to play hide and seek with fate and the song and the sound offer an idyllic landscape. For this reason we rarely broadcast (to the limited radio imagination) our deepest acoustic preoccupations, and the diasporic music that collective listening generates is not always guarded by anything besides generational memory.

In the West the only thing more jarring than being free-spirited enough to make something up as you go along and enjoy it, is the confidence to not spy on yourself while doing it, to not maintain a record of exactly what happened, to not write it down or find some other form in which to engrave every nuance of every event into a lifeless monument.

In Black culture the record is the memory and the memory is the body, so the record is the body, and when it changes form, the spirit, the soul, the feeling and stories and teachings are passed down body to body like trusts without much fear that they will be lost. Even now, as we are lost, we’re not always inclined to create static archives that might lead us back someplace that makes sense. Our archives have always been alive, entities, capricious and at risk and traveling with us and guarding our sense of meaning, the sonic territory we can draw from no matter where we happen to find ourselves, this way nothing ever really goes missing, there is no myth that cannot be repopulated and reborn in any moment. Though spiritually this makes us versatile giants, economically in America it means we don’t always possess the mixture of opportunism and self-esteem that inspires us to keep track of our sh*t in a culture that uses formal recordkeeping as another excuse for the distribution of capital and real estate.

“Listening, knowing one another by sound and voice, is the first law of black liberation—without this skill there is no self-preservation.”At the same time I realized that the distribution of land and resources in the US was often manipulated by large institutions that invest a lot of money into buying archives, creating exclusive portals through which documented history can be accessed and studied and changed, I saw that my family’s ransacked home and all of the missing parts of my father’s legacy revealed more than just circumstance. With all of that information scattered among estranged family members, a man’s story becomes compartmentalized, eventually forgotten, unless someone does the work of telling it, recording it, gathering it all back in one place, as sound, as verbal action, as music’s own memory, as more music, as better listening.

For black people of the diaspora, that place is often on a vinyl record, because the truth for us remains in the sound. That box of tapes my dad left opened up a life of listening to the recorded voices of black people, developing almost pathological kinship with resonant timbres, and a feeling of brotherhood, sisterhood, toward people I had only heard on a record or tape.

Eventually, after years and years of that practice, I started making my own archives, assembling recordings of black voices in ways that defy typical archival logic simply because the data collecting is improvised and at the mercy of in-the-moment human interaction, what I can grab from one basement or closing record depot—our archives, like our listening, will be collectively improvised. When we finally accept the value of keeping autonomous records of our histories, and demand places to keep those records, places we ourselves own and run, when that demand is universal for diasporic artists, it will be collective improvisation, our shared black technology, that stirs it and ensures our success, lets us tonally recover what has been materially erased or made into ruins. We can make music with those ruins, reanimate them, listen and speak them into new forms.

V.

A Brief History of My Improvised Listening

Stevie Wonder’s Ribbon in the Sky

One of the first songs I remember hearing and listening to for hours on end was Stevie Wonder’s Ribbon in Sky. I was learning a dance to it and I think sometimes I left out a step on purpose so that my instructor would have to rewind the tape, because I loved that song that much. At home with my Walkman™ I would pace my room and mark the dance and trace the imaginary ribbon with my eyes like some kind of cat entranced by her own leash. I was a prisoner of the song’s somber fantasy and I loved waiting for the divots in Stevie’s tone—I loved the pacing, the whole composition. I guess it’s the first time I remember a song soothing a void I had otherwise ignored, filling in a missing space, running toward me in the dark carrying visions of my father and his mother, and that happy broken home in Iowa transported to Hollywood on the edge of Stevie’s we won’t lose, with love on our side.

Jimmy Holiday I’m Gonna Use What I Got, To Get What I Need

Dad wasn’t just singing, he was crying and bargaining with eternity. To me, he had always been a king, always been glorious and formidable and in charge of everything, so hearing my dad talk about being born in a shack and struggling, and needing something from the world, was devastating and a relief. I heard this song on one of those tapes we managed to get away with, and I wore it out, studied it. I wanted to protect the boy he had been on that white man’s farm picking cotton, making weight, with no school to attend. I wanted to console him when he hopped a train to Louisiana and started recording and had to find women enamored enough to sit up nights and listen to him sing and write down the songs because he could not write them himself, had not been allowed the time to learn to read or write.

Eleven words that hit me like daggers. Dad had suffered, had been afraid, wounded, neglected, and was afraid to be loved even after all of his success. He remained, psychologically, the young black boy from the country who just wants to sing into the comfort of night and feel free. Listening to my dad describe prevailing over deprivation, I understood the interplay of vulnerability and violence he had used as a survival tactic; I observed men like him at every level of society, male archetypes who had to pretend to be tough and unruly in order to hide their dangerous sincerity.

Minnie Ripperton’s Loving You

I learned this ballad for another ballet solo, this one en pointe. I wore a cherry red unitard and stiff red pointe shoes to match, and was meant to glide across the dance floor like an erotic young nymph, an apparition, someone impossible, at least that’s what I told myself. I decided I was redefining beauty and the weightless bourrees and unwound turnings were my physical manifesto, my way of using my body to tell the world that I loved myself after all, that that love came easy, that I could relax and listen to birds chirping and not worry about some great tragedy lurking behind that mindless bliss.

Loving you, is easy ‘cause you’re beautiful, and everything that I do, is out of loving you. Dedicating this song and solo to myself made it clear to me that I needed my own love and attention, and also made me feel like a desired object of that universal gaze—I felt redeemed and more self-possessed than ever before in all that dance’s bloodred confidence. I didn’t know a black singer could sound so carefree, the way Minnie did, no grinding on her throat, no foreboding blues, just soft almost dainty relishing in common emotion. A new way of being was made available to me with her song, a happy disguise or a part of myself I felt the world unworthy of, my rapacious joy, the part of me I expose when I’m dancing had an analog in Minnie’s soft voicings, of pure unfettered romance.

Billie Holiday

In college, she was all I could hear over the self-important rhetoric of my philosophy seminars. I’d leave some critical theory course where we’d spent three hours discussing Freud’s concept of the Death Drive as it relates to warring nations in the throes of late capitalism, and I’d be nauseated. Did this compulsive violence deserve the dignity of high concepts? Not in my estimation. If we’re gonna talk about self-made martyrs and epic self-destruction fueled by displaced love and tenderness without talking about Billie Holiday we’re gonna be liars forever. Her crackling and medicinal tone was how I made it through that indoctrination in western thinking that we call a college education. Don’t get me wrong, I loved Foucault and Derrida and Joyce and them, but without Billie Holiday I might have told everyone about themselves more often than I already did (that white boyfriend I had to dump because he said, verbatim, “who actually listens to Billie Holiday,” like black culture was some kind of Disneyland and she was a mascot for his idea of it, acted shocked that anyone could be that misguided). I urge everyone to listen to “Strange Fruit” or “I Cover the Waterfront ” while reading Plato’s Apology and not believe in miracles.

Miles Dewey Do what he says Davis

His voice is broken, gutted, a grammar of aching gashes, but when Miles Davis says My father’s rich and my mother’s good looking, I have never suffered and I don’t intend to suffer and I can play the blues, I forgive everyone for about five minutes and tell all my friends to get rich and scream this through the open roofs of convertibles and it’s lit.

James Baldwin

When YouTube democratized listening and looking beyond the capacity of radio and television, I spent months listening to James Baldwin speak. I had found my other father, another prophetic Jimmy, in the most unlikely corner of the digital omniverse—how had I gone so long without hearing a voice like that? After Baldwin, I found Sun Ra and Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Amiri Baraka and Nina Simone and Lorraine Hansberry and Abbey Lincoln, speaking out loud, healing my sense of story and of cadence and oratory as a practice. The meta language that can be heard, the breath or slight cough or rustle of fabric, all of that poetry felt like gold, felt like the first time I heard my dad cry I’m gonna use what I got, to get what I need.

Midnight Girl

When I was in grad school and a friend was helping me digitize some of my tapes, I found a recording of my dad singing at home in Iowa. It’s my favorite love song of all time because it feels like it’s for me, for my mother, for my sisters, for all women who feel in some way abandoned by convention. It’s a song about permission to not belong to a man, to recognize when you have more to forge than romance and its specific kind of alienation—in a way it’s him saying goodbye and also saying I’m here always, deliberate, intentional.

*

Good read found on the Lithub

Comments

Post a Comment